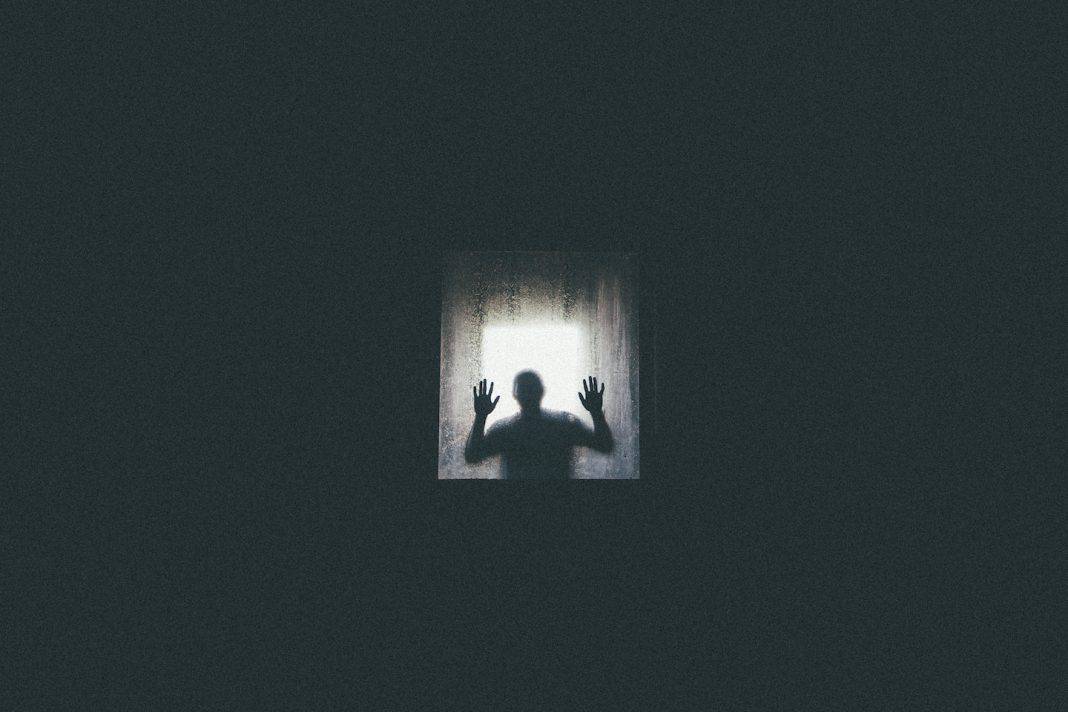

“I called what I did white-knuckling. I would appear to be fine, making jokes, concealing my internal battle.” Ashleigh Ostermann, 27, has had anxiety and depression for as long as she can remember. But she recalls it really started to affect her life back in middle school. “I was always anxious, irrationally so,” she says. “It was something more than being ‘sad.’” On the outside, she appeared bubbly, funny, and smart. “I was told that I ‘didn’t look depressed’ because I always had a smile on my face.” “In reality, I was barely holding on.” Many people still think of mental health disorders as a choice—placing blame on the individual. And it’s this narrow view of mental illness as a character flaw that accounts—at least in part—for the fact that only half of people with mental illness receive treatment, despite tens of millions of Americans being affected each year, according to the National Institute of Mental Health. Living with mental illness often means putting on a brave face. It means struggling with an invisible condition others often fail to grasp. “My illness is just invisible,” says Ostermann, “which freaks people out. If they can’t see or understand it, then it must be fake, right?” What we need now more than ever is to hear stories from the inside.

Anxiety: A Mind That Doesn’t Stop

“I didn’t want to be seen as a ‘crazy person,’ so I suffered in silence for years,” says 31-year-old NYC resident Stephanie Morris, who recalls initially denying her anxiety symptoms when they first appeared in her early twenties. “I would wake up daily with anxiety attacks,” she says. “My mind would race, and I would often be paralyzed.” Her symptoms also included regular meltdowns in her work bathroom as well as a host of others like dizziness, shakiness, shortness of breath, fatigue, and rashes. “Anxiety is a normal part of being human,” says Don Mordecai, MD, National Leader for Mental Health and Wellness at Kaiser Permanente. But he says there’s cause for concern when the worry is accompanied by physical symptoms, as in Morris’ case. He mentions other signs to look for, including restlessness, sleep problems, a sense of trouble breathing, and so on. Anxiety disorders are the most common mental illness in the U.S., affecting 40 million American adults—or 18.1 percent of the population—every year. While many people conflate occasional nervousness with being anxious, this is different from the worry that comes from public speaking or preparing for a test. Generalized anxiety disorder involves persistent levels of anxiety that cause significant distress or impairment for the person dealing with it, says Mordecai, who is also a spokesperson for Kaiser Permanente’s national awareness effort, Find Your Words. “The goal [of Find Your Words] is to create a culture of acceptance and support, and help end the stigma of mental health conditions,” Mordecai says. Indeed, more spaces that allow for these kinds of conversations are needed. Ostermann gives the parallel of someone who breaks their arm: “They go to a doctor and get treatment.”

Bipolar Disorder: Living With Perpetual Jet Lag

“You’d never know I have it,” Krista says. “I have to hide it from most people, because I’m worried the stigma will affect my work life.” Krista, who chose not to use her real name, says living with bipolar 1 disorder is like living with perpetual jet lag. The anxiety sometimes makes her want to jump out a window, but she won’t. “My medications saved my life and have made it possible for me to live a normal, healthy life and sleep well—but side effects have also left me chronically groggy,” Krista explains. “My husband calls me Sleeping Beauty.” She says she sleeps ten to eleven hours each night. “I hate that, but it’s a small price to pay for my mental health.” Characterized by dramatic shifts in mood, energy, and activity levels, bipolar disorder affects approximately 5.7 million adults in the United States. There are two main classifications of bipolar disorder: bipolar 1 and bipolar 2. Bipolar 1 is known for particularly strong manic episodes, and bipolar 2 is known for particularly strong depressive episodes. A third type, cyclothymic disorder, is similar to bipolar 2 but lower in intensity. The societal understanding of bipolar disorder is still fraught with myths. Many people associate it with a Jekyll-Hyde personality, but in fact, the average bipolar patient is more often depressed than manic, according to Gary Sachs, MD, director of the Bipolar Clinic and Research Program at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. Popular depictions of the mental illness generally involve off-the-wall characterizations; normalizing bipolar disorder amid a culture that throws the term around like an insult seems like a daunting task. But Krista wants others to know that a diagnosis isn’t the end of the world. “It’s the beginning of a better life.” In addition to taking her medications, she also exercises, goes to therapy, and receives acupuncture treatments. More importantly, she has access to a team of mental health professionals and support from family and friends, which have made all the difference. “I have to fight to stay well,” Krista admits. “I just wish there were more people out there talking about those of us who are doing well, rather than all the negative stereotypes,” she says. “Stigma keeps us quiet.” Mordecai agrees. “For some, a diagnosis can be a troubling confirmation that something is wrong with them. They can feel the stigma of mental illness, and this can lead to even worse feelings about oneself.” He notes, however, that for some people, diagnosis can bring relief in the knowledge that their condition is known, shared, understood by others. “With this knowledge can come a sense of control over the condition and the ability to take action to feel better.”

Borderline Personality Disorder: A Different Normal

“Some days, I’m so active, and sometimes I can barely get out of bed.” Richard Kaufman, 49, wishes people would realize that living with mental illness isn’t just feeling blue or something you can easily snap out of. “I think other people see me as just fine—they won’t really understand my normal.” After getting hurt on active duty, the New Jersey-based veteran was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), traumatic brain injuries, and borderline personality disorder. While those first two were a result of his time in the military, the latter gave him new insight into his past. “I started to understand why I was so different as a child, enduring severe abandonment issues which I still have to this day,” Kaufman explained. “Now I understand why sometimes I had no feelings at all and then sometimes I was all feelings.” In fact, people with borderline personality disorder experience intense episodes of anger, depression, and anxiety that can last from a few hours to days. They also tend to view things in extremes, such as all good or all bad. According to Mordecai, this kind of alteration of the sense of self that happens with some conditions is something that people who have not lived with mental health conditions can find hard to understand. He says he sometimes hears patients say they aren’t sure what normal is. “They have lived with a mental health condition so long, it has changed their sense of self.”

PTSD: Trying to Stay Even-Keeled

“I know it’s not easy on my wife [when] I’m balls to the wall,” Kaufman notes. Despite medication and attending therapy, he says his greatest challenge is staying even-keeled. “Some days are awesome—some, not so much.” PTSD affects 7.7 million American adults. According to the Man O’ War Project, a university-led research trial at Columbia University Irving Medical Center, 1 in 5 veterans are affected by PTSD and account for 18 percent of all deaths by suicide among adults in the U.S. The disorder generally develops after experiencing a shocking, frightening, or dangerous event, as Kaufman went through during active duty. This fear triggers many split-second changes in the body as a response. While many who encounter trauma will eventually recover from these symptoms, those who feel stressed or frightened even when they’re no longer in imminent danger are experiencing PTSD. Trying to function while in the grips of mental illness is a tenuous balance, and this is not lost on Mordecai. “One of the most profound things I see every day is people living with mental health conditions with tremendous grace and resilience,” he says. “They are sometimes frustrated, especially when symptoms come back after going away for some time, but for the most part, they go on with their lives and do what they can to feel better.”

Depression: Feeling Sad Without Reason

“I know what it’s like to be laying on the bathroom floor, eyes swollen, tears streaming down my face, certain that the pain will never end,” Ostermann explains. “Not able to see the light at the end of the tunnel—to be sad for no reason other than not being able to help it.” Despite being one of the most prevalent mental disorders in the U.S., depression is still highly stigmatized and poorly understood. Much of the public sentiment regarding the disorder is that a person should simply “get over” their feelings of sadness. Most don’t realize that major depressive disorder, for example, is the leading cause of disability in the U.S. for ages 15 to 44.3. Even when a person is able to find a treatment that works, it can be challenging to encounter the normal ups and downs of daily life because a bad day might be the beginning of another depressive episode, Mordecai says. “People need to relearn who they are without a mental health condition. The way someone perceives the world and themselves in it can be very different when they are, for instance, depressed.” It can take time to rediscover the undepressed self, he says. But he also notes the mental health condition is something a person manages, not who they are. “Fortunately, people are very resilient. They are parents, spouses, friends, co-workers, students—people—first.”

Semicolon; When Your Story Isn’t Over

“Mental illness can’t be cured in the way that other illnesses can,” Ostermann notes. “Not yet, anyway. So it’s something I have lived with and learned to manage.” She believes part of her success comes from the willingness to admit when she needs help and knowing she is in control of what defines who she is as a person. “I acknowledge that my life isn’t perfect. That I’m not perfect. But I will not let anything get in the way of my dreams.” A few years ago, she had a semicolon tattooed on her wrist. “It serves as a reminder that my story isn’t over.” More than anything, she wants others to know they aren’t alone. “I’m here to say that I’m not the only one who has gone through this and the more that we talk about mental illness, the more we break the stigma.”